Volume 15, No.3 Pages 157 - 162

1. 最近の研究から/FROM LATEST RESEARCH

Long-term Proposal Report:

Nuclear Resonance Vibrational Spectroscopy (NRVS) of Iron-Sulfur Enzymes for Hydrogen Metabolism, Nitrogen Fixation, & Photosynthesis

[1]Department of Applied Science, University of California, Davis, [2]Physical Biosciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, [3]Department of Biochemistry, Virginia Polytechnic Institute, [4]School of Agriculture, Nagoya University, [5]Max-Planck Institut für Bioanorganische Chemie, [6]Department of Chemical Engineering, Stanford University, [7]SPring-8/JASRI

Introduction

Fe-S proteins serve a wide variety of essential tasks in living systems, including electron transfer within proteins, catalysis of chemical reactions, sensing of the chemical environment, regulation of DNA expression, repair of damaged DNA, and maintenance of molecular structure[1][1] "Structure, function, and formation of biological iron-sulfur clusters.", Johnson, D. C.; Dean, D. R.; Smith, A. D.; Johnson, M. K. Ann. Rev. Biochem., 2005, 74, 247-281.. The significance of understanding the structure and function of these proteins can hardly be overstated. We have been studying Fe-S enzymes that catalyze some of biology’s most important reactions. The fixation of molecular N2 to two molecules of NH3 by nitrogenase supplies the chemically reactive N needed for building proteins and nucleic acids. In photosynthetic bacteria and green algae, the reduction of protochlorophyllide to chlorophyllide a creates a key light-trapping molecule for biological photosynthesis. This reaction is catalyzed by dark-operative protochlorophyllide reductase (DPOR), an enzyme with significant homology to nitrogenase. The production or consumption of molecular H2 by hydrogenase is as fast as the best artificial fuel cells, but uses earth-abundant Fe instead of rare and expensive Pt. Overall, Fe-S enzymes help shape our environment and make life as we know it feasible.

NRVS

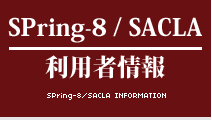

Mössbauer spectroscopy provides chemical information about a sample from small changes in nuclear transition energies. This is possible because for some events, the recoilless fraction f, a γ-ray is absorbed without energy transfer to molecular vibrations or phonons. On the other hand, in the recoil fraction (1-f), nuclear transitions do couple to vibrations. Metal-ligand stretching and bending frequencies range from ~50 - 2000 cm-1, or ~ 6 − 250 meV. These values are orders of magnitude greater than hyperfine splittings, and vibrations are not directly observed in conventional Mössbauer spectroscopy. However, as shown in Figure 2, vibrational transitions are observed in NRVS experiments at 3rd generation synchrotron radiation sources such as SPring-8. NRVS is exciting for studies of Fe-S enzymes because it provides an isotope selective vibrational spectrum. Only modes that involve displacement of the 57Fe nucleus couple to the nuclear transition. The fraction Φ of the excitation probability S(ν) that goes into a transition is proportional to the fraction of kinetic energy due to 57Fe in the given vibrational mode. In a typical NRVS experiment, such as at SPring-8 beamline 9, an undulator is the source of x-rays, which are filtered to a bandpass of 1 eV by a premonochromator. A second high-resolution monochromator then narrows the bandpass to ~ 1 meV. An avalanche photodiode (APD) with ~ 1 ns time resolution detects delayed Fe fluorescence and distinguishes it from scattered radiation.

Figure 1 Key enzymes in this study. Top: BchNB (catalytic unit of darkoperative proto-chlorophyllide reductase (left) vs. (right) N2ase MoFe protein[2][2] "X-ray crystal structure of the light-independent protochlorophyllide reductase", Muraki, N.; Nomata, J.; Ebata, K.; Mizoguchi, T.; Shiba, T.; Tamiaki, H.; Kurisu, G.; Fujita, Y. Nature, 2010, 465, 110-U124.; lower left: clusters in [NiFe] H2ase and highlighted [NiFe]-cluster, lower right: intact [FeFe] H2ase and highlighted H-cluster.

Figure 2 Left: Main NRVS regions. Ordinate is ‘counts’. Right: NRVS for Fe-H/D vibrations.

Nitrogenase

Biological nitrogen fixation, involving reduction of dinitrogen to ammonia, is the key reaction in the nitrogen cycle and the ultimate source for most N in living systems, via the reaction[3][3] "Structural basis of biological nitrogen fixation", Rees, D. C.; Tezcan, F. A.; Haynes, C. A.; Walton, M. Y.; Andrade, S.; Einsle, O.; Howard, J. B. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A, 2005, 363, 971–984.:

N2 + 8H+ + 8e- + 16MgATP → 2NH3 + H2 + 16MgADP + 16Pi

In Azotobacter vinelandii (Av) the Mo-dependent N2ase that accomplishes this reaction uses electrons from an Fe4S4 cluster in an α2 ‘Fe protein’ (Av2) to reduce a larger α2β2 ‘MoFe protein’ (Av1). Within Av1, an Fe8S7 ‘P-cluster’ supplies electrons to the active site MoFe7S9 ‘FeMo-cofactor’ (Figure 1)[4][4] "Crystallographic Structure and Functional Implications of the Nitrogenase Molybdenum-Iron protein from Azotobacter vinelandii", Kim, J. K.; Rees, D. C. Nature, 1992, 360, 553-560.. There are also N2-reducing enzymes based on VFe- or even FeFe-cofactors.

As a prelude to studying the more difficult topic of N2 binding, we chose to first examine the better-defined complexes of N2ase with CO. The inhibition of nitrogen fixation by CO has been known since at least 1941[5][5] "Mechanism of Biological Nitrogen Fixation. VIII. Carbon Monoxide as an Inhibitor for Nitrogen Fixation by Red Clover", Lind, C. J.; Wilson, P. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1941, 63, 3511-3514.. The nature of CO interactions with N2ase has an added significance because there are (unpublished) reports of hydrocarbon synthesis (Fischer-Tropsch chemistry) during CO reactions with VFe N2ase. CO inhibits the reduction of N2 and other substrates reversibly and non-competitively[6][6] "Inhibition of Nitrogenase-Catalyzed Reductions", Hwang, J. C.; Chen, C. H.; Burris, R. H. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1973, 292, 256-270., at micromolar concentrations and on a sub-second time scale consistent with the rate of electron transfer[7][7] "Stopped-Flow Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Allows Continuous Monitoring of Azide Reduction, Carbon Monoxide Inhibition, and ATP Hydrolysis by Nitrogenase", Tolland, J. D.; Thorneley, R. N. F. Biochemistry, 2005, 44, 9520-9527.. CO does not, however, inhibit H2 evolution by N2ase so that, under CO, N2ase effectively becomes an ATP-dependent hydrogenase.

Exposure of N2ase to CO during turnover elicits species with a variety of EPR signals, namely ‘lo-CO’, ‘hi-CO’, and ‘hi(5)-CO’, depending on the partial pressure of CO ([CO])[7][7] "Stopped-Flow Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Allows Continuous Monitoring of Azide Reduction, Carbon Monoxide Inhibition, and ATP Hydrolysis by Nitrogenase", Tolland, J. D.; Thorneley, R. N. F. Biochemistry, 2005, 44, 9520-9527.. Each of these species and its characteristic EPR signal is described by the [CO] required for its formation[8,9][8] "Investigation of CO Binding and Release from Mo-Nitrogenase during Catalytic Turnover", Cameron, L. M.; Hales, B. J. Biochemistry, 1998, 37, 9449–9456.

[9] "Mechanistic Features and Structure of the Nitrogenase α-Gln195 MoFe Protein", Sørlie, M.; Christiansen, J.; Lemon, B. J.; Peters, J. W.; Dean, D. R.; Hales, B. J. Biochemistry, 2001, 40, 1540–1549.. The ‘hi-CO’ species that we have chosen to examine by NRVS has an axial EPR signal (g-values near 2.17 and 2.06) and is formed under a [CO] many times higher than required for substrate inhibition. This ‘hi-CO’ N2ase is reported to contain two CO molecules bound to the FeMo-cofactor[10][10] "CO Binding to the FeMo Cofactor of CO-inhibited Nitrogenase: 13CO and 1H Q-band ENDOR Investigation", Lee, H.-I.; Cameron, L. M.; Hales, B. J.; Hoffman, B. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1997, 119, 10121-10126..

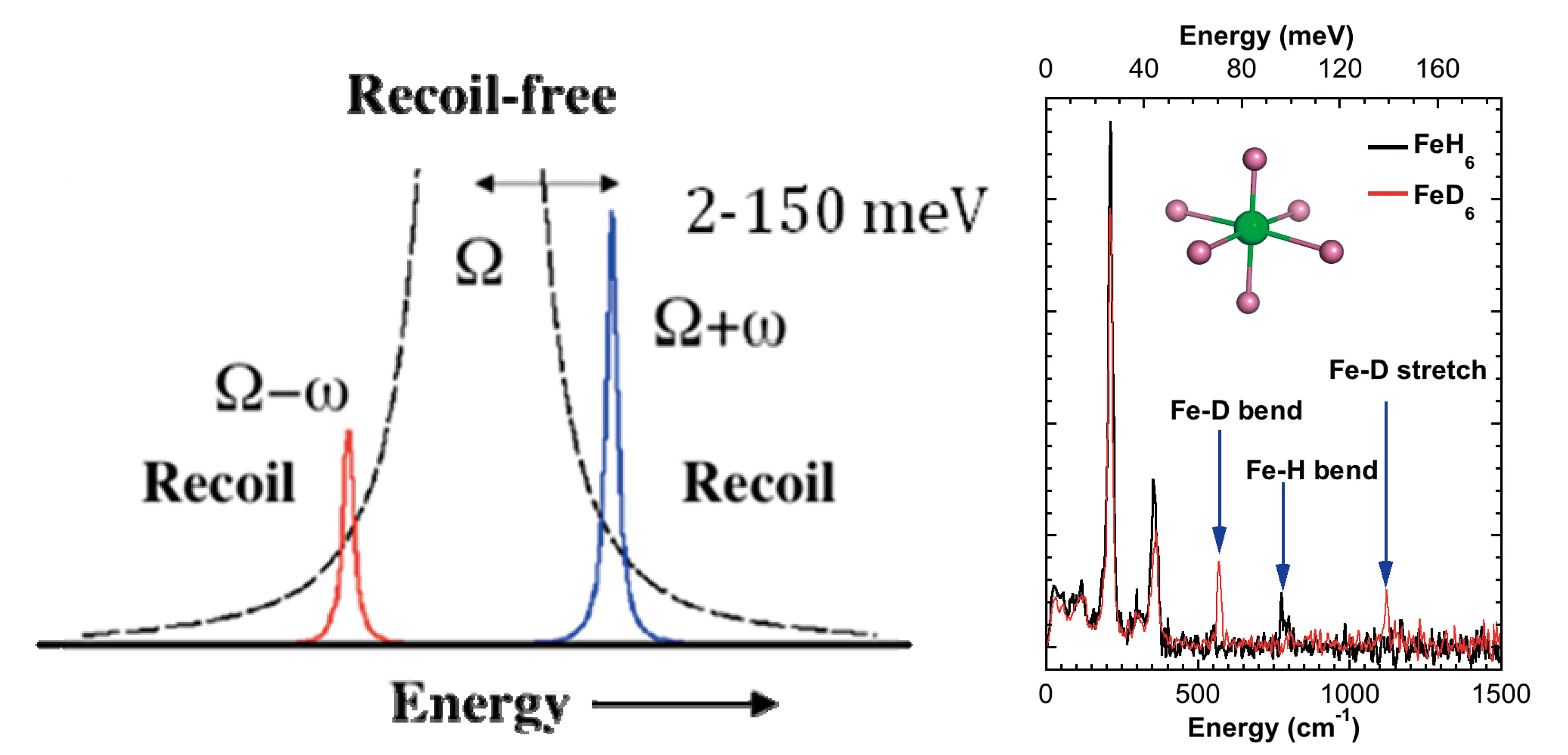

As illustrated in Figure 3, we have been able to observe distinct changes in N2ase NRVS upon treatment to produce the ‘hi-CO’ species. There was a significant loss in intensity in the peak around 190 cm-1. In the past we associated this region with cluster ‘breathing’ modes[11][11] "How Nitrogenase Shakes - Initial Information about P-Cluster and FeMo-Cofactor Normal Modes from Nuclear Resonance Vibrational Spectroscopy (NRVS)", Xiao, Y.; Fisher, K.; Smith, M. C.; Newton, W.; Case, D. A.; George, S. J.; Wang, H.; Sturhahn, W.; Alp, E. E.; Zhao, J.; Yoda, Y.; Cramer, S. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2006, 128, 7608-7612., and it is clear that these are affect by CO binding. More informative (and difficult to see) is the development of a band at 508 cm-1 that we associate with Fe-CO stretching. Although there have been numerous indirect studies implicating binding at Fe, the NRVS is the first data to unambiguously prove and characterize the strength of the Fe-CO bonding. In collaborations with theorists Case, Noodleman, and Pelmentschikov, we have pursued a theoretical DFT analysis of the N2ase CO interaction, and this has yielded the structure proposed in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Left: N2ase FeMo cofactor NRVS with (―) and without (―) CO. Ordinate represents 57Fe partial vibrational density of states. Arrows indicate direction of change with CO. Right: DFT-based structure for proposed CO/CHO complex.

BchNB

As illustrated in Figure 1, the enzyme DPOR has a protein structure quite similar to N2ase. However, instead of the P-cluster and FeMo cofactor, as part of its active site it uses a special [4Fe-4S] cluster, with 3 cysteine and 1 aspartate ligands (Figure 4). It turns out that we had already studied a small ferredoxin with the same ligation – Pyrococcus furious ferredoxin (Pf Fd). Although there are broad similarities in their NRVS, there are also significant differences, and our goal is to understand what is special about the DPOR cluster. Of particular interest is a band just above 50 meV (> 400 cm-1) that may be associated with Fe-O (Asp) stretching. In Pf Fd it has been proposed that a ‘carboxylate shift’ occurs with this residue upon protein reduction[12][12] "Accurate Computation of Reduction Potentials of 4Fe-4S Clusters Indicates a Carboxylate Shift in Pyrococcus furiosus Ferredoxin", Jensen, K. P.; Ooi, B.-L.; Christensen, H. E. M. Inorg. Chem., 2007, 46, 8710-8716..

Figure 4 Left: Comparison of NRVS for Pyrococcus furiosus ferredoxin (―) and DPOR BchNB protein (―). Right: Structure of the [4Fe-4S] cluster, showing special sidechain (D36)[2][2] "X-ray crystal structure of the light-independent protochlorophyllide reductase", Muraki, N.; Nomata, J.; Ebata, K.; Mizoguchi, T.; Shiba, T.; Tamiaki, H.; Kurisu, G.; Fujita, Y. Nature, 2010, 465, 110-U124..

Hydrogenases

In living organisms, H2 uptake and evolution is accomplished by the enzyme H2ase[13][13] "Hydrogenases: active site puzzles and progress", Armstrong, F. A. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol., 2004, 8, 133-140.:

2H+ + 2e- ![]() H2.

H2.

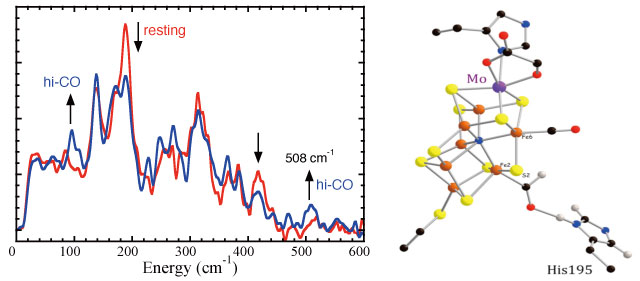

There are three phylogenetically unrelated H2ases[14][14] "Classification and phylogeny of hydrogenases", Vignais, P. M.; Billoud, B.; Meyer, J. FEMS Microbiol. Rev., 2001, 25, 455-501.: [NiFe][15][15] "[NiFe]-hydrogenases: spectroscopic and electrochemical definition of reactions and intermediates", Armstrong, F. A.; Albracht, S. P. J. Philos. Transact. A, 2005, 363, 937-954., [FeFe][16][16] "Fe-only hydrogenases: structure, function and evolution", Nicolet, Y.; Cavazza, C.; Fontecilla-Camps, J. C. J. Inorg. Biochem., 2002, 91, 1-8., and [Fe] H2ases[17][17] "The crystal structure of C176A mutated Fe -hydrogenase suggests an acyl-iron ligation in the active site iron complex", Hiromoto, T.; Ataka, K.; Pilak, O.; Vogt, S.; Stagni, M. S.; Meyer-Klaucke, W.; Warkentin, E.; Thauer, R. K.; Shima, S.; Ermler, U. FEBS Lett., 2009, 583, 585-590.. Apart from their biochemical significance, these enzymes have generated intense technological interest because of their relevance for a future H2 economy[13][13] "Hydrogenases: active site puzzles and progress", Armstrong, F. A. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol., 2004, 8, 133-140.. [NiFe] H2ases are found in many bacteria and archaea, and in these enzymes, catalysis occurs at an unusual [Ni-Fe] cluster (Figure 5)[18][18] "Structural differences between the ready and unready oxidized states of [NiFe] hydrogenases", Volbeda, A.; Martin, L.; Cavazza, C.; Matho, M.; Faber, B. W.; Roseboom, W.; Albracht, S. P.; Garcin, E.; Rousset, M.; Fontecilla-Camps, J. C. J. Inorg. Biochem., 2005, 10, 239-249.. The catalytic sites of [FeFe] H2ases contain an ‘H-cluster’, comprised of a [4Fe-4S] cluster bridged to a unique [2Fe]H subcluster (Figure 5). These [FeFe] H2ases are among the most efficient H2 catalysts known, with Kcat values that range up to 6000 molecules of H2 s-1[19][19] "The Structure and Mechanism of Iron-hydrogenases", Adams, M. W. W. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1990, 1020, 115-145.. Crystal structures of two types of [FeFe] H2ase, CpI from C. pasteurianum and DdH from D. desulfuricans, have been solved[16,20][16] "Fe-only hydrogenases: structure, function and evolution", Nicolet, Y.; Cavazza, C.; Fontecilla-Camps, J. C. J. Inorg. Biochem., 2002, 91, 1-8.

[20] "X-ray Crystal Structure of the Fe-Only Hydrogenase (CpI) from Clostridium pasteurianum to 1.8 Angstrom Resolution", Peters, J. W.; Lanzilotta, W. N.; Lemon, B. J.; Seefeldt, L. C. Science, 1998, 282, 1853-1858.. [Fe] H2ase, also known as Hmd, catalyzes the transfer of a hydride ion from H2 to methenyl-H4MPT+, yielding methenyl-H4MPT+. Originally thought to be ‘metal-free’, it is now known to contain an Fe bound by 2 CO molecules and an organic cofactor (Figure 5)[17][17] "The crystal structure of C176A mutated Fe -hydrogenase suggests an acyl-iron ligation in the active site iron complex", Hiromoto, T.; Ataka, K.; Pilak, O.; Vogt, S.; Stagni, M. S.; Meyer-Klaucke, W.; Warkentin, E.; Thauer, R. K.; Shima, S.; Ermler, U. FEBS Lett., 2009, 583, 585-590..

Figure 5 Left to right: (A) [NiFe] H2ase active site structure. (B) [FeFe] H2ase structure. (C) Recently revised structure of Hmd [Fe] H2ase, highlighting Fe-acyl coordination[17][17] "The crystal structure of C176A mutated Fe -hydrogenase suggests an acyl-iron ligation in the active site iron complex", Hiromoto, T.; Ataka, K.; Pilak, O.; Vogt, S.; Stagni, M. S.; Meyer-Klaucke, W.; Warkentin, E.; Thauer, R. K.; Shima, S.; Ermler, U. FEBS Lett., 2009, 583, 585-590..

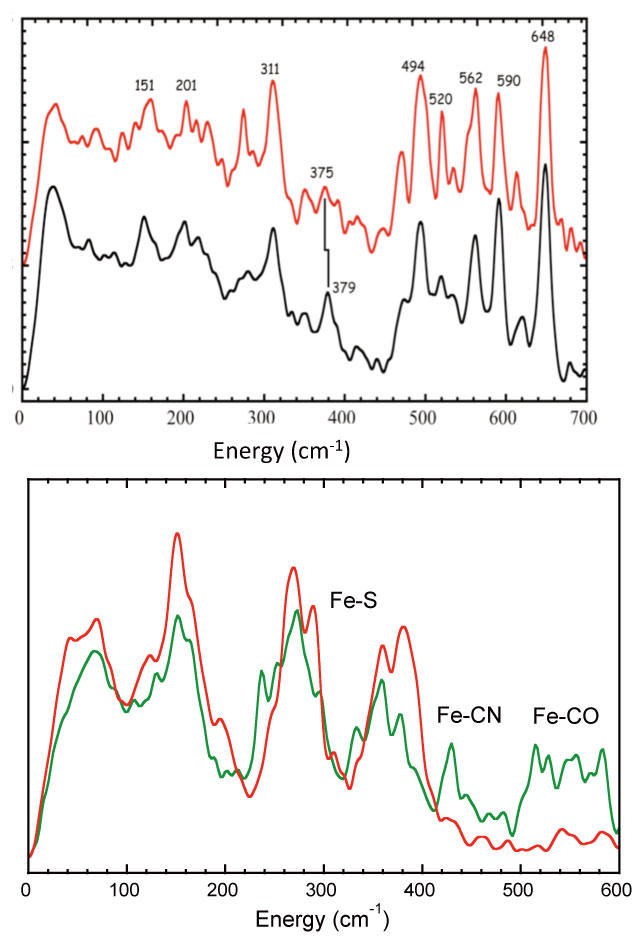

During the course of our project we examined all three types of H2ase. Since Hmd [Fe] H2ase has only one type of Fe, with two CO ligands, it presented especially strong NRVS in the high frequency region (Figure 6). Although we originally expected 4 Fe-CO modes (from two coupled Fe-CO bend and two coupled Fe-CO stretch modes), we saw a more complicated pattern with at least 6 strong bands. We now believe the additional features arise from coupling with Fe-CO modes for the acyl coordination recently discovered in the revised crystal structure (Figure 5). We also saw evidence for an exchangeable water ligand with Fe-O mode at 379 cm-1.

Figure 6 Left: The strong Fe-CO bend and stretch modes (494 - 649 cm-1) in [Fe] H2ase. The 379 - 375 cm-1 shift is assigned to 18O-substituted H2O in the latter sample. Right: Fe-CX features in NRVS of fully enriched [NiFe] H2ase vs. selectively enriched [FeFe] H2ase. In both figures ordinates represent 57Fe partial vibrational density of states.

We next examined the more difficult [NiFe] and [FeFe] H2ases. Although the [NiFe] H2ase has only one active site Fe in the presence of 11 other Fe-S cluster Fe (Figure 1). We were still able to see very weak features between 500 and 600 cm-1 due to Fe-CO bend and stretch modes (Figure 6). Even more promising, when 57Fe is selectively incorporated into the H-cluster of CPI H2ase, the Fe-CN and Fe-CO modes are clearly visible. We hope to use NRVS on both systems, both to characterize catalytic intermediates and also (using isotopic labeling of biosynthetic precursors) to track and define the biosynthesis of the active sites.

Summary & Conclusion

We have found NRVS to be an extremely valuable spectroscopic probe of Fe-S proteins. Our preliminary surveys have shown that weak Fe-ligand interactions can be seen in the presence of the dominant Fe-S cluster signals. In the future, with more flux and better resolution, we hope to use NRVS to define the catalytic mechanisms of many of these important enzymes.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by NIH GM-65440, NSF CHE-0745353, and the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research. We thank SPring-8 and JASRI for support of beam time.

References

[1] "Structure, function, and formation of biological iron-sulfur clusters.", Johnson, D. C.; Dean, D. R.; Smith, A. D.; Johnson, M. K. Ann. Rev. Biochem., 2005, 74, 247-281.

[2] "X-ray crystal structure of the light-independent protochlorophyllide reductase", Muraki, N.; Nomata, J.; Ebata, K.; Mizoguchi, T.; Shiba, T.; Tamiaki, H.; Kurisu, G.; Fujita, Y. Nature, 2010, 465, 110-U124.

[3] "Structural basis of biological nitrogen fixation", Rees, D. C.; Tezcan, F. A.; Haynes, C. A.; Walton, M. Y.; Andrade, S.; Einsle, O.; Howard, J. B. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A, 2005, 363, 971–984.

[4] "Crystallographic Structure and Functional Implications of the Nitrogenase Molybdenum-Iron protein from Azotobacter vinelandii", Kim, J. K.; Rees, D. C. Nature, 1992, 360, 553-560.

[5] "Mechanism of Biological Nitrogen Fixation. VIII. Carbon Monoxide as an Inhibitor for Nitrogen Fixation by Red Clover", Lind, C. J.; Wilson, P. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1941, 63, 3511-3514.

[6] "Inhibition of Nitrogenase-Catalyzed Reductions", Hwang, J. C.; Chen, C. H.; Burris, R. H. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1973, 292, 256-270.

[7] "Stopped-Flow Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Allows Continuous Monitoring of Azide Reduction, Carbon Monoxide Inhibition, and ATP Hydrolysis by Nitrogenase", Tolland, J. D.; Thorneley, R. N. F. Biochemistry, 2005, 44, 9520-9527.

[8] "Investigation of CO Binding and Release from Mo-Nitrogenase during Catalytic Turnover", Cameron, L. M.; Hales, B. J. Biochemistry, 1998, 37, 9449–9456.

[9] "Mechanistic Features and Structure of the Nitrogenase α-Gln195 MoFe Protein", Sørlie, M.; Christiansen, J.; Lemon, B. J.; Peters, J. W.; Dean, D. R.; Hales, B. J. Biochemistry, 2001, 40, 1540–1549.

[10] "CO Binding to the FeMo Cofactor of CO-inhibited Nitrogenase: 13CO and 1H Q-band ENDOR Investigation", Lee, H.-I.; Cameron, L. M.; Hales, B. J.; Hoffman, B. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1997, 119, 10121-10126.

[11] "How Nitrogenase Shakes - Initial Information about P-Cluster and FeMo-Cofactor Normal Modes from Nuclear Resonance Vibrational Spectroscopy (NRVS)", Xiao, Y.; Fisher, K.; Smith, M. C.; Newton, W.; Case, D. A.; George, S. J.; Wang, H.; Sturhahn, W.; Alp, E. E.; Zhao, J.; Yoda, Y.; Cramer, S. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2006, 128, 7608-7612.

[12] "Accurate Computation of Reduction Potentials of 4Fe-4S Clusters Indicates a Carboxylate Shift in Pyrococcus furiosus Ferredoxin", Jensen, K. P.; Ooi, B.-L.; Christensen, H. E. M. Inorg. Chem., 2007, 46, 8710-8716.

[13] "Hydrogenases: active site puzzles and progress", Armstrong, F. A. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol., 2004, 8, 133-140.

[14] "Classification and phylogeny of hydrogenases", Vignais, P. M.; Billoud, B.; Meyer, J. FEMS Microbiol. Rev., 2001, 25, 455-501.

[15] "[NiFe]-hydrogenases: spectroscopic and electrochemical definition of reactions and intermediates", Armstrong, F. A.; Albracht, S. P. J. Philos. Transact. A, 2005, 363, 937-954.

[16] "Fe-only hydrogenases: structure, function and evolution", Nicolet, Y.; Cavazza, C.; Fontecilla-Camps, J. C. J. Inorg. Biochem., 2002, 91, 1-8.

[17] "The crystal structure of C176A mutated Fe -hydrogenase suggests an acyl-iron ligation in the active site iron complex", Hiromoto, T.; Ataka, K.; Pilak, O.; Vogt, S.; Stagni, M. S.; Meyer-Klaucke, W.; Warkentin, E.; Thauer, R. K.; Shima, S.; Ermler, U. FEBS Lett., 2009, 583, 585-590.

[18] "Structural differences between the ready and unready oxidized states of [NiFe] hydrogenases", Volbeda, A.; Martin, L.; Cavazza, C.; Matho, M.; Faber, B. W.; Roseboom, W.; Albracht, S. P.; Garcin, E.; Rousset, M.; Fontecilla-Camps, J. C. J. Inorg. Biochem., 2005, 10, 239-249.

[19] "The Structure and Mechanism of Iron-hydrogenases", Adams, M. W. W. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1990, 1020, 115-145.

[20] "X-ray Crystal Structure of the Fe-Only Hydrogenase (CpI) from Clostridium pasteurianum to 1.8 Angstrom Resolution", Peters, J. W.; Lanzilotta, W. N.; Lemon, B. J.; Seefeldt, L. C. Science, 1998, 282, 1853-1858.