Volume 12, No.4 Pages 314-322

2. 最近の研究から/FROM LATEST RESEARCH

Nuclear Resonance Vibrational Spectroscopy (NRVS) of Iron – Sulfur Enzymes for Nitrogen Fixation and Hydrogen Metabolism

Project Leader:

Stephen P. Cramer (Department of Applied Science, University of California, Davis and Physical Biosciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Professor)

Project Member:

Simon J. George (Physical Biosciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Research Scientist)

Yisong Guo (Department of Applied Science, University of California, Davis, PhD Student)

Matt C. Smith (Department of Applied Science, University of California, Davis, Postdoctoral)

Hongxin Wang (Department of Applied Science, University of California, Davis, Research Scientist)

Yuming Xiao (Department of Applied Science, University of California, Davis, PhD Student)

1. Introduction

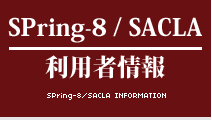

Iron containing metalloproteins play key roles in many important biochemical processes. Our research focuses on two critical iron-sulfur enzymes-nitrogenase and hydrogenase. Nitrogenase (N2ase) catalyzes the reduction of dinitrogen to ammonia and this biological ammonia synthesis is responsible for about half of the protein available for human consumption[1][1] B. E. Smith, R. L. Richards and W. E. Newton: Catalysis for Nitrogen Fixation - Nitrogenases, Relevant Chemical Models and Commerical Processes. Springer (2004).. Hydrogenase (H2ase) catalyzes the evolution (or consumption) of dihydrogen. H2 catalysis is crucial for the metabolism of many anaerobic organisms, and knowledge about the mechanism of H2 evolution may prove critical for a future hydrogen economy[2][2] K. A. Vicent, J. A. Cracknell, A. Parkin and F. A. Armstrong: Hydrogen cycling by enzymes: electrocatslysis and implications for future energy technology. Dalton Trans. (2005) 3397-3403.. Although scientists have studied N2ase and H2ase for a long time, with significant progress especially after crystal structures of these metalloenzymes came out in 1990s (Figure 1), there are still lots of fundamental questions left such as where substrates bind and interact with these proteins and how structures of active sites change during the course of catalytic cycle.

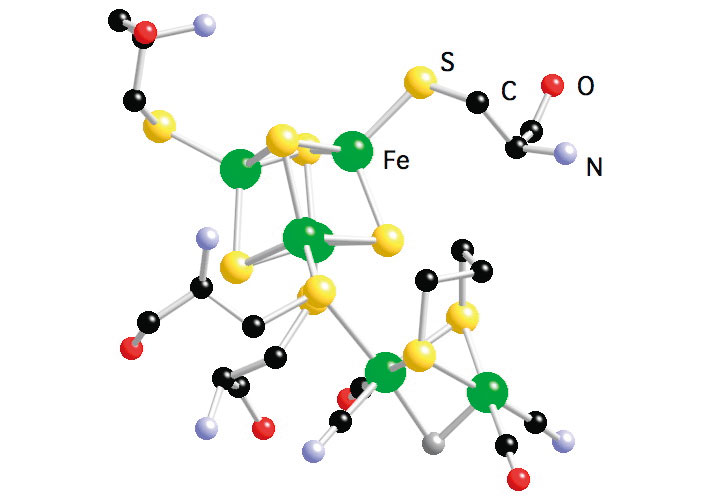

Figure 1. Bioinorganic chemist's view of N2ase and H2ase. Left to right: clusters in (a) Mo N2ase[3][3] O. Einsle, F. A. Tezcan, S. L. A. Andrade, B. Schmid, M. Yoshida, J. B. Howard and D. C. Rees: Nitrogenase MoFe-Protein at 1.16 Å Resolution: A Central Ligand in the FeMo-Cofactor. Science 297(2002) 1696-1700., (b) [NiFe] H2ase, including 'distal', 'medial', and 'proximal' Fe-S clusters[4][4] A. Volbeda, M. H. Charon, C. Piras, E. C. Hatchikian, M. Frey and J. C. FontecillaCamps: Crystal Structure of the Nickel-Iron Hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio gigas. Nature 373(1995) 580-587., (c) C. pasteurianum [FeFe] H2ase[5][5] J. W. Peters, W. N. Lanzilotta, B. J. Lemon and L. C. Seefeldt: X-ray Crystal Structure of the Fe-Only Hydrogenase (CpI) from Clostridium pasteurianum to 1.8 Angstrom Resolution. Science 282(1998) 1853-1858..

Nuclear resonance vibrational spectroscopy (NRVS) is a relatively new technique that became available as a spectroscopic method because of third generation synchrotron source and development of x-ray optics with sub-meV resolution[6][6] J. T. Sage, C. Paxson, G. R. A. Wyllie, W. Sturhahn, S. M. Durbin, P. M. Champion, E. E. Alp and W. R. Scheidt: Nuclear resonance vibrational spectroscopy of a protein active-site mimic. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 13(2001) 7707-7722.. It involves scanning an extremely monochromatic x-ray beam through a nuclear resonance. Apart from the familiar'zero phonon'Mössbauer resonance, there are additional transitions that correspond to nuclear excitation in combination with excitation (Stokes) or de-excitation (anti-Stokes) of vibrational modes. The measurement technique exploits the relatively long lifetime of the nuclear excitation, along with the pulsed nature of the synchrotron source, by electronically gating on Fe Kα emission that occurs following internal conversion in between synchrotron pulses. Compared to other well-established vibrational spectroscopic techniques such as infrared spectroscopy and Raman scattering, the biggest advantage of NRVS is its site selectivity. NRVS is only sensitive to vibrations of Mössbauer nuclei (in our case, 57Fe). It means now we can observe vibrations of Fe atoms at the active site of N2ase and H2ase while ignoring interference from other part of proteins.

The goal of our program is to use NRVS to answer structural and dynamical issues of these proteins that are beyond the reach of other methods. We expect to have better understanding of (a) the structure and dynamics of N2ase and H2ase, (b) how these enzymes are biosynthesized and ultimately (c) their molecular mechanism of catalysis. This information may eventually prove useful for development of synthetic small molecule 'mimics' that can catalyze the same reactions.

2. Experimental

57Fe NRVS spectra were recorded using published procedures at Beamline 09-XU at SPring-8, Japan[7][7] Y. Yoda, M. Yabashi, K. Izumi, X. W. Zhang, S. Kishimoto, S. Kitao, M. Seto, T. Mitsui, T. Harami, Y. Imai and S. Kikuta: Nuclear resonant scattering beamline at SPring-8. Nuclear Instruments & Methods in Physics Research Section A-Accelerators Spectrometers Detectors & Associated Equipment 467(2001) 715-718.. During the 3-year period of this long-term proposal, improvements were achieved on both high heat-load pre-monochromator and high resolution monochromator. Experimental resolution was improved from 3.5 meV to 1.1 meV that is proving sufficient to resolve most of the NRVS details. The flux was 〜3 × 109 in a 1.1 meV bandwidth, using a liquid nitrogen-cooled Si(1,1,1) double crystal monochromator followed by asymmetrically cut Ge(4,2,2) and two Si(9,7,5) crystals. During NRVS measurements, samples were maintained at low temperatures using liquid He cryostats. Temperatures were calculated using the ratio of anti-Stokes to Stokes intensity according to: S(-E) = S(E)exp(-E/kT). Nuclear fluorescence and Fe K fluorescence (from internal conversion) were recorded with an APD array at SPring-8[8][8] S. Kishimoto, Y. Yoda, M. Seto, S. Kitao, Y. Kobayashi, R. Haruki and T. Harami: Array of avalanche photodiodes as a position-sensitive x-ray detector. Nuclear Instruments & Methods In Physics Research Section A 513(2004) 193-196..

3. Results

3.1 Rubredoxin

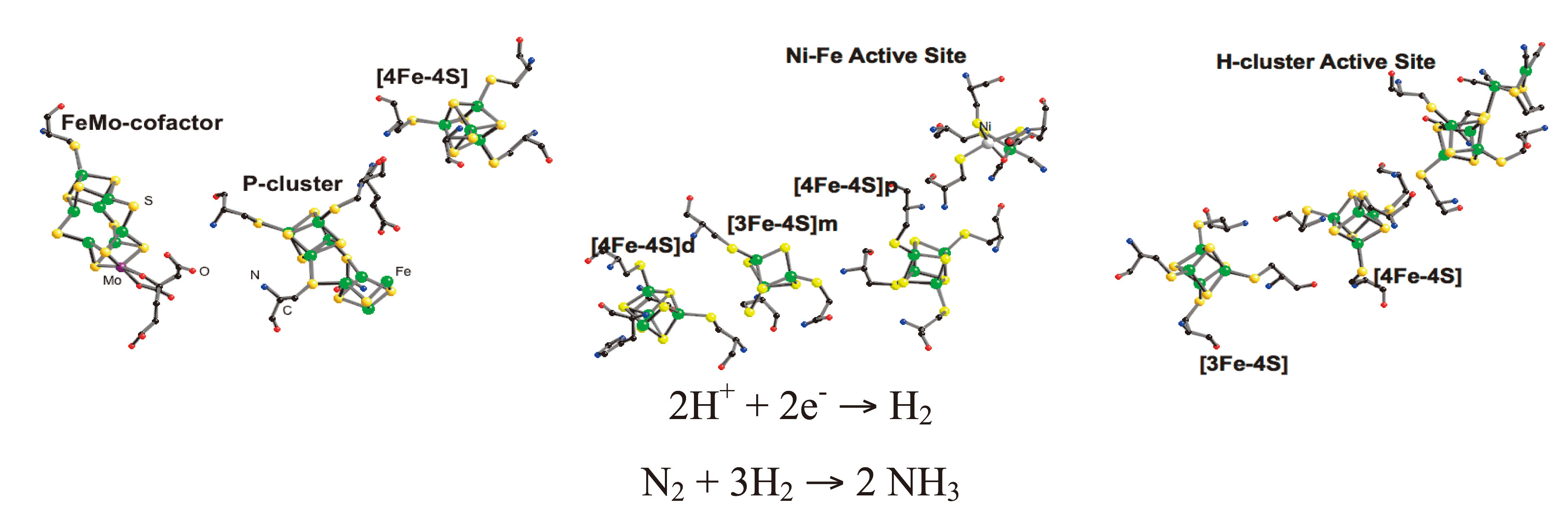

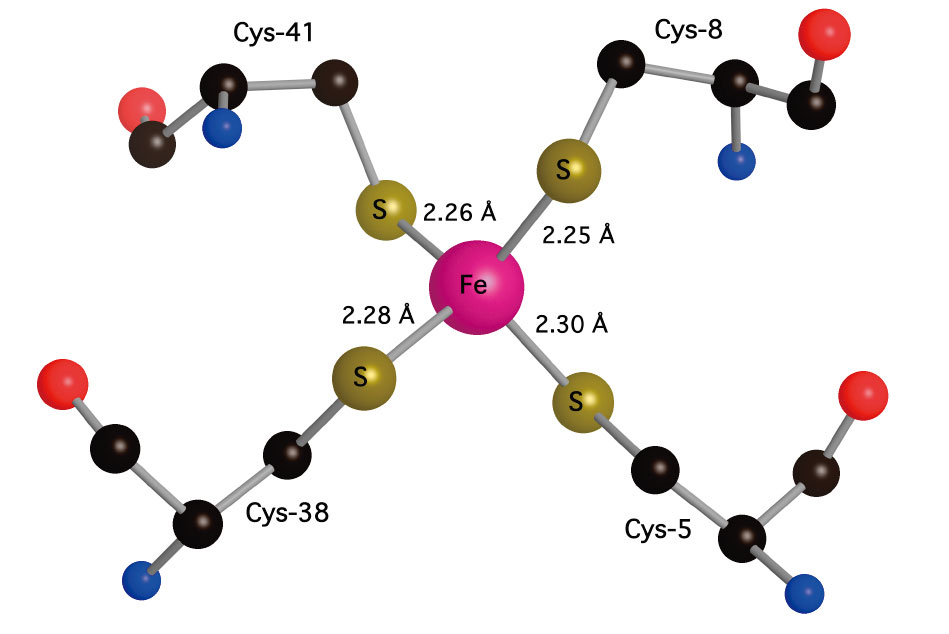

Rubredoxins are small (〜50 amino acid) electron-transfer proteins that contain a single Fe(S-cys)4 redox center[9][9] J. Meyer, and J.-M. Moulis: Rubredoxin, in Handbook of Metalloproteins (A. Messerschmidt and R. Huber, Eds.) Wiley, New York. (2001) pp505-517.. Apart from their role in specific biological catalytic reactions, rubredoxins serve as model systems for understanding the factors that determine reduction potentials in metalloprotein. High-resolution x-ray crystal structures of different rubredoxins all reveal a roughly tetrahedral FeS4 site, often described as approaching D2d symmetry via a compression along an S4 axis (Figure 2). In Pf Rd, this distortion results in 2 compressed (〜103±1°) (Cys5S-Fe-SCys41 and Cys8S-Fe-SCys41) and 4 expanded (〜111-114°) S-Fe-S angles; there are also 2 shorter Fe-S bond lengths (2.25-2.26 Å) (Fe-SCys8 and Fe-SCys41) and 2 slightly longer Fe-S bonds (2.28-2.30 Å) (Fe-SCys5 and Fe-SCys38)[10][10] R. Bau, D. C. Rees, D. M. Kurtz, R. A. Scott, H. S. Huang, M. W. W. Adams and M. K. Eidsness: Crystal structure of rubredoxin from Pyrococcus furiosus at 0.95Å resolution, and the structures of N-terminal methionine and formylmethionine variants of Pf Rd. Contributions of N-terminal interactions to thermostability. Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry 3(1998) 484-493..

Figure 2. Left: 'Pymol' representation of oxidized Pf Rd, including sticks for cysteine residues, illustrating exposed location of Fe site (red). Right: 'Crystalmaker' close-up of Fe site showing slight compression of Fe-SCys8 and Fe-SCys41 bonds and distinction between 〜90° FeSCC dihedral angles for 'exposed' cysteines and 〜180° FeSCC dihedral angles fort 'buried' cysteines (PDB code 1BRF).

The dynamical properties of the oxidized and reduced Fe sites play an important role in the redox properties of rubredoxins. Previous Resonance Raman work had shown an asymmetric Fe-S stretch region divided into 3 bands near 350-370 cm-1 [11][11] R. S. Czernuszewicz, L. K. Kilpatrick, S. A. Koch and T. G. Spiro: Resonance Raman Spectroscopy of Iron(III) Tetrathiolate Complexes: Implications for the Conformation and Force Field of Rubredoxin. Journal of the American Chemical Society 116(1994) 1134-1141. and in our Raman spectra we observed these and additional bands out to 440 cm-1. The NRVS was very broad in this region, suggesting that stretching modes are strongly coupled with protein side chain motion. A model with 5-atom chains extending from the Fe site was required to quantitatively reproduce the Fe-S stretch region-quite similar to Goddard's 'chromophore in protein'model. In the reduced rubredoxin, strong asymmetric Fe-S modes were shifted to 300-320 cm-1. This is the first observation of Fe-S stretching modes in a reduced Rd[12][12] Y. Xiao, H. Wang, S. J. George, M. C. Smith, M. W. W. Adams, J. Francis E. Jenney, W. Sturhahn, E. E. Alp, J. Zhao, Y. Yoda, A. Dey, E. I. Solomon and S. P. Cramer: Normal Mode Analysis of Pyrococcus furiosus Rubredoxin via Nuclear Resonant Vibrational Spectroscopy (NRVS) and Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. Journal of the American Chemical Society 127(2005) 14596 -14606..

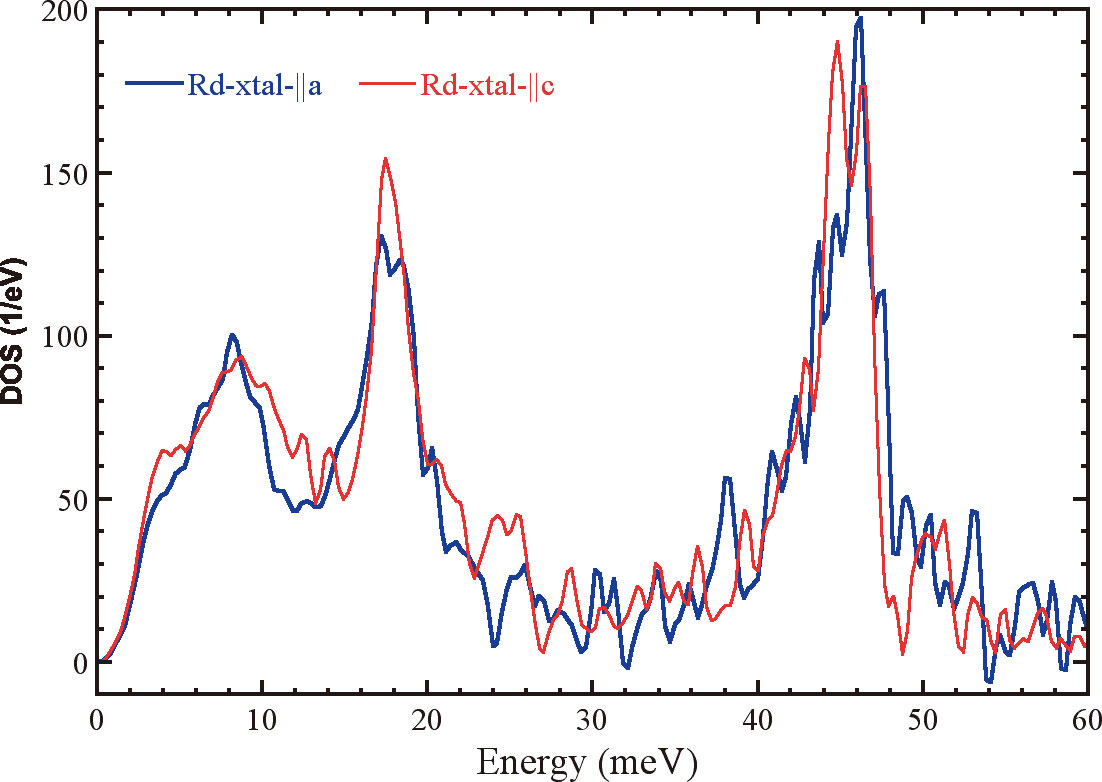

Very recently, we have preformed our first single crystal NRVS measurements on a rubredoxin crystal. Large (1 mm2) crystals were grown in collaboration with Prof. Robert Bau (University of Southern California). The data are excellent and clearly show an orientation dependence in the Fe-S stretches (Figure 3). We are proposing that the higher frequency stretching modes are associated with the shorter Fe-S bond lengths.

Figure 3. Orientation dependent NRVS spectra of rubredoxin single crystal.

3.2 Nitrogenase

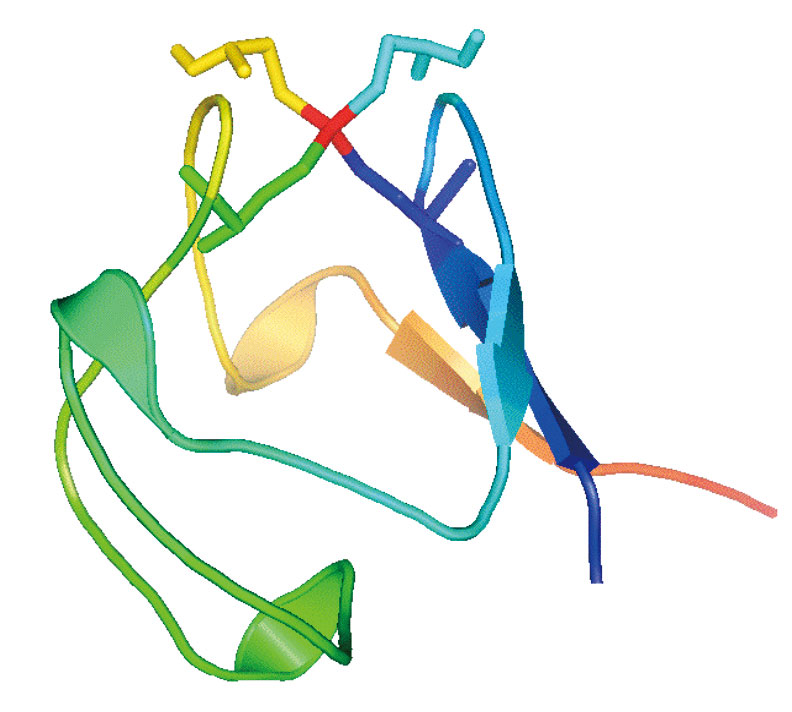

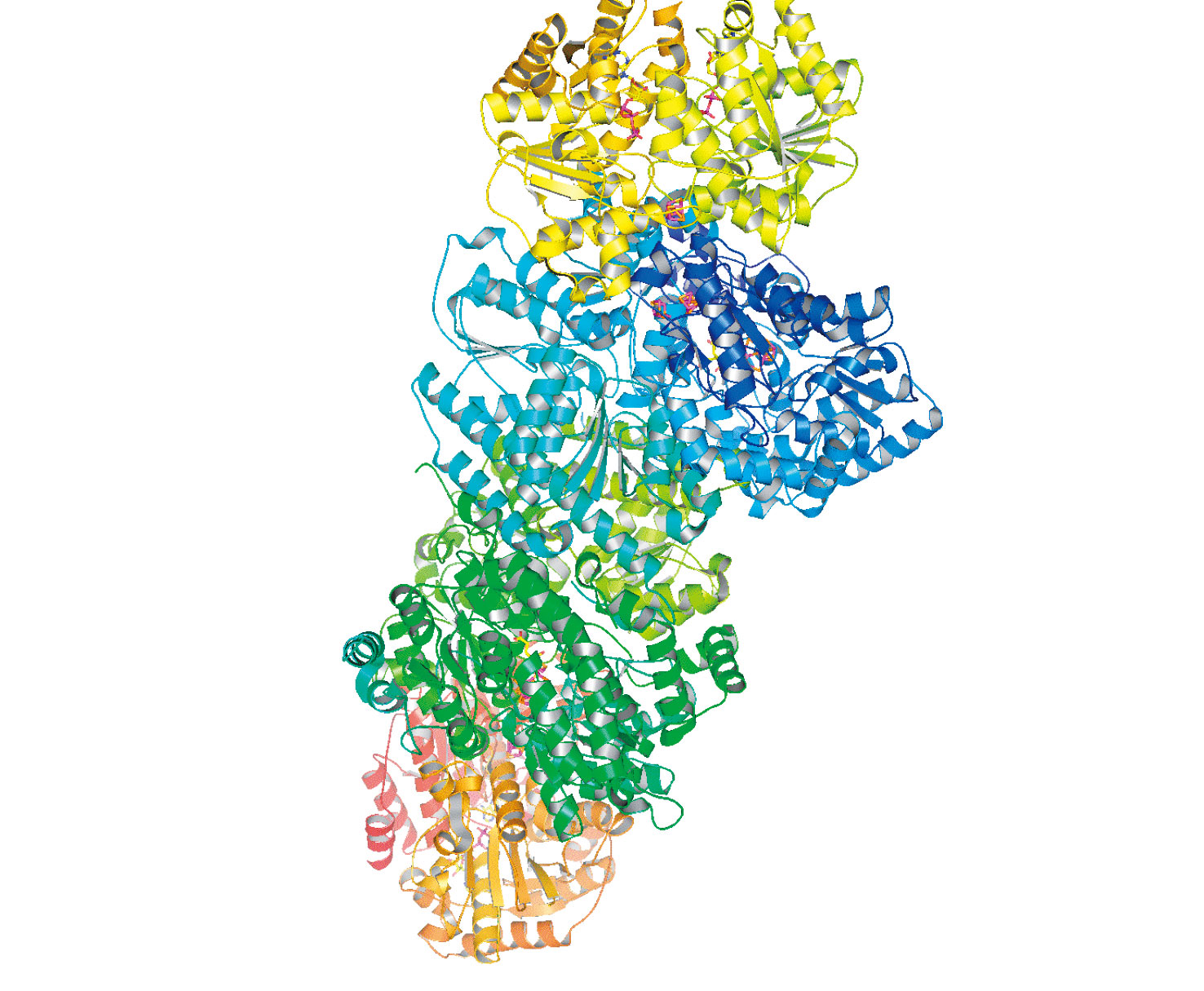

Biological nitrogen fixation, involving reduction of dinitrogen to ammonia, is the key reaction in the nitrogen cycle[1][1] B. E. Smith, R. L. Richards and W. E. Newton: Catalysis for Nitrogen Fixation - Nitrogenases, Relevant Chemical Models and Commerical Processes. Springer (2004).. In Azotobacter vinelandii (Av) the Mo-dependent nitrogenase (N2ase) consists of two metallproteins: Fe protein (Av2) and MoFe protein (Av1) (Figure 4). The 〜63 kDa Fe protein is a dimer of two identical subunits bridged by a single [4Fe-4S] cluster. In addition to binding the [4Fe-4S] cluster, the second principal functional feature of the Fe-protein is to bind nucleotides, MgATP and MgADP. During catalysis, the Fe protein provides electrons to MoFe protein in a MgATP-dependent reaction and is the only know reductant that will support substrate reduction by the MoFe protein. The 〜230 kDa MoFe protein is composed of two identical dimers (α2β2) that each consist of two different metal clusters, the iron-molybdenum cofactor (FeMo-co) and the P cluster. The FeMo-cofactor, which locates in a cleft of the a-subunit, is the active center where substrates bind and react with the enzyme and can be extracted into organic solvent. The P-cluster is buried at the interface between α-subunit and β-subunit and is believed to be the first electron acceptor from Fe-protein and transport electrons to the FeMo-cofactor[13][13] D. C. Rees, F. A. Tezcan, C. A. Haynes, M. Y. Walton, S. Andrade, O. Einsle and J. B. Howard: Structural basis of biological nitrogen fixation. Philosophical TRANSACTIONS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF LONDON SERIES A 363(2005) 971-984..

Figure 4. Cartoon representation of the nitrogenase complex. Top and bottom are Fe proteins (yellow and orange); middle is MoFe protein (blue and green). (PDB 1G21)

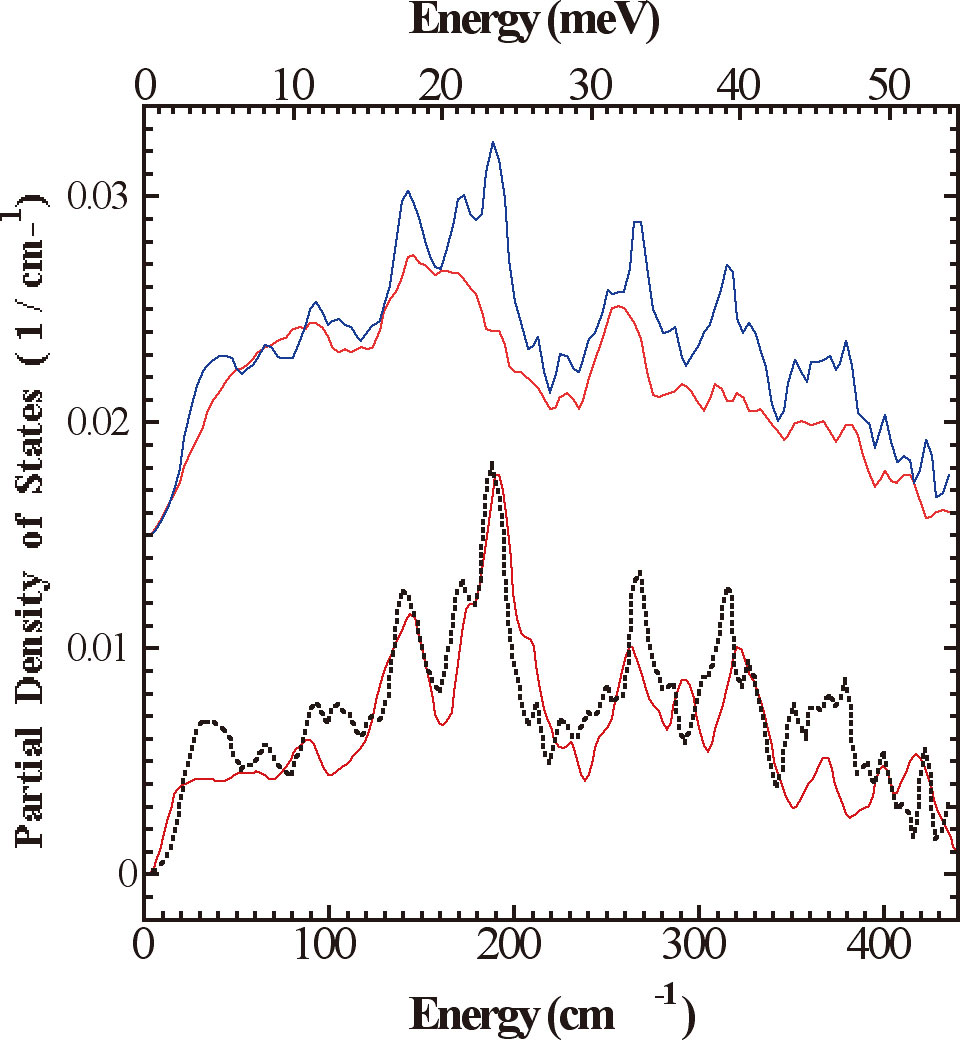

A recent structure for Av1 at 1.16 Å resolution[3][3] O. Einsle, F. A. Tezcan, S. L. A. Andrade, B. Schmid, M. Yoshida, J. B. Howard and D. C. Rees: Nitrogenase MoFe-Protein at 1.16 Å Resolution: A Central Ligand in the FeMo-Cofactor. Science 297(2002) 1696-1700. revealed electron density at the center of the trigonal prismatic cage of Fe atoms in the FeMo-cofactor, and hence an overall MoFe7S9X core cluster composition. The electron density is consistent with a light (C, N, or O) atom. Characterization of the interstitial atom is essential for understanding both the biosynthesis of the FeMo-cofactor and the mechanism of nitrogenase. We have used NRVS to study the dynamics of the Fe-S clusters in nitrogenase. The catalytic site FeMo-cofactor exhibits a strong signal near 190 cm-1, where conventional Fe-S clusters have weak NRVS (Figure 5). This intensity is ascribed to cluster breathing modes whose frequency is raised by an interstitial atom. A variety of Fe-S stretching modes are also observed between 250 and 400 cm-1. This work is the first spectroscopic information about the vibrational modes of the intact nitrogenase FeMo-cofactor and P-cluster and support the presence of an interstitial atom in both isolated FeMoco and in the Av1-bound FeMo-cofactor[14][14] Y. Xiao, K. Fischer, M. C. Smith, W. Newton, D. A. Case, S. J. George, H. Wang, W. Sturhahn, E. E. Alp, J. Zhao, Y. Yoda and S. P. Cramer: How Nitrogenase Shakes - Initial Information about P-Cluster and FeMo-Cofactor Normal Modes from Nuclear Resonance Vibrational Spectroscopy (NRVS). Journal of the American Chemical Society 128(2006) 7608-7612..

Figure 5. Experimental 57Fe PVDOS functions, DFe (![]() ) , for (top to bottom) (a) Av1 (

) , for (top to bottom) (a) Av1 (![]() ) vs. ΔnifE Av1 (

) vs. ΔnifE Av1 (![]() ); (b) Av1-ΔnifE:Av1 difference spectrum (

); (b) Av1-ΔnifE:Av1 difference spectrum (![]() ) vs. isolated FeMoco (

) vs. isolated FeMoco (![]() ).

).

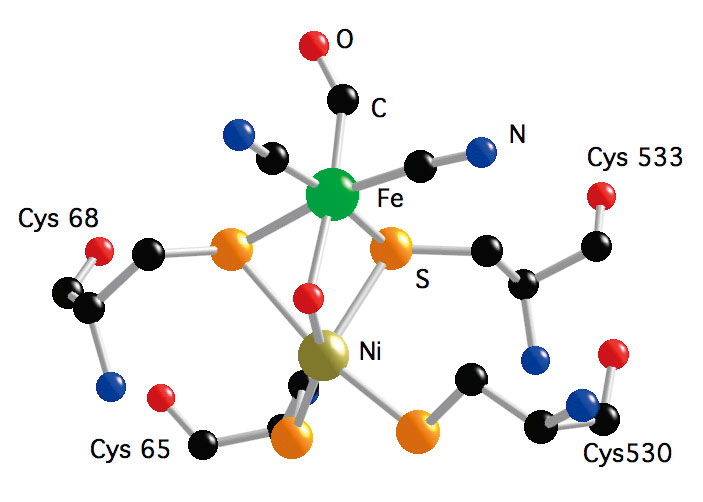

3.3 Hydrogenase

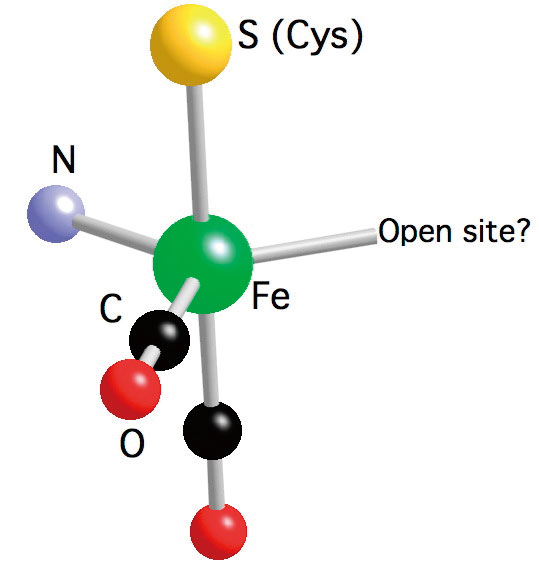

Hydrogen (H2) metabolism occurs in a large variety of micro-organisms, such as methanogenic, sulfate-reducing, fermentative, nitrogen-fixing, photosynthetic bacteria, where H2 activation is catalyzed by hydrogenases (H2ases) following the reaction: H2 ![]() 2H++2e-. H2ases are among the most efficient H2 catalysts known, with turn over rate ranging up to 6000 molecules of H2 per second[15][15] M. Frey : Hydrogenases: Hydrogen-Activating Enzymes. ChemBioChem 3(2002) 153-160.. There are three classes of H2ases − [NiFe] H2ases[4][4] A. Volbeda, M. H. Charon, C. Piras, E. C. Hatchikian, M. Frey and J. C. FontecillaCamps: Crystal Structure of the Nickel-Iron Hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio gigas. Nature 373(1995) 580-587. (including a [NiFeSe] subset), [FeFe] H2ases[5][5] J. W. Peters, W. N. Lanzilotta, B. J. Lemon and L. C. Seefeldt: X-ray Crystal Structure of the Fe-Only Hydrogenase (CpI) from Clostridium pasteurianum to 1.8 Angstrom Resolution. Science 282(1998) 1853-1858., and Fe-S cluster-free H2ases (Hmd)[16][16] S. Shima and S. K. Thauer: A Third Type of Hydrogenase Catalyzing H2 Activation. The Chemical Record 7(2007) 37-46.. [NiFe] H2ases, which contain Ni-Fe dinuclear catalytic center, are mostly involved in H2 oxidation, while [FeFe] H2ases, which contain Fe-Fe dinuclear catalytic center, are mostly involved in H2 production. Hmd H2ases, which were thought to be 'metal free', are now found to have a Fe mononuclear catalytic center. The enzymes catalyze the reversible reduction of methenyltetrahydromethanopterin (methenyl-H4MPT) to methylene-H4MPT using H2. The comparison of the active site structures (Figure 6) of the three types of H2ases has revealed common features, which is the Fe sites are all terminally bound with nonprotein hexogenous diatomic ligands CO and/or CN-. This is an indication of convergent evolution, and the structure similarities are most probably essential for an efficient activation of H2. During this long-term proposal period, we have studied the active sites of these three types of H2ases in different enzyme states using NRVS along with some inorganic model complexes.

2H++2e-. H2ases are among the most efficient H2 catalysts known, with turn over rate ranging up to 6000 molecules of H2 per second[15][15] M. Frey : Hydrogenases: Hydrogen-Activating Enzymes. ChemBioChem 3(2002) 153-160.. There are three classes of H2ases − [NiFe] H2ases[4][4] A. Volbeda, M. H. Charon, C. Piras, E. C. Hatchikian, M. Frey and J. C. FontecillaCamps: Crystal Structure of the Nickel-Iron Hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio gigas. Nature 373(1995) 580-587. (including a [NiFeSe] subset), [FeFe] H2ases[5][5] J. W. Peters, W. N. Lanzilotta, B. J. Lemon and L. C. Seefeldt: X-ray Crystal Structure of the Fe-Only Hydrogenase (CpI) from Clostridium pasteurianum to 1.8 Angstrom Resolution. Science 282(1998) 1853-1858., and Fe-S cluster-free H2ases (Hmd)[16][16] S. Shima and S. K. Thauer: A Third Type of Hydrogenase Catalyzing H2 Activation. The Chemical Record 7(2007) 37-46.. [NiFe] H2ases, which contain Ni-Fe dinuclear catalytic center, are mostly involved in H2 oxidation, while [FeFe] H2ases, which contain Fe-Fe dinuclear catalytic center, are mostly involved in H2 production. Hmd H2ases, which were thought to be 'metal free', are now found to have a Fe mononuclear catalytic center. The enzymes catalyze the reversible reduction of methenyltetrahydromethanopterin (methenyl-H4MPT) to methylene-H4MPT using H2. The comparison of the active site structures (Figure 6) of the three types of H2ases has revealed common features, which is the Fe sites are all terminally bound with nonprotein hexogenous diatomic ligands CO and/or CN-. This is an indication of convergent evolution, and the structure similarities are most probably essential for an efficient activation of H2. During this long-term proposal period, we have studied the active sites of these three types of H2ases in different enzyme states using NRVS along with some inorganic model complexes.

Figure 6. Active site structure of NiFe H2ase from D. gigas (left); Active site structure of FeFe H2ase from D. deculfuricans (middle); and Model of the active site structure of Hmd H2ase from M. marburgensis (right).

3.3.1 Hmd H2ase

The Hmd H2ase we studied is from the methanogenic archaeon Methanothermobacter marburgensis (DSMZ2133). The structure of the active site is not yet known, the recent IR [17][17] E. J. Lyon, S. Shima, R. Boecher, R. K. Thauer, F.-W. Grevels, E. Bill, W. Roseboom and S. P. J. Albracht: Carbon Monoxide as an Intrinsic Ligand to Iron in the Active Site of the Iron-Sulfur-Cluster-Free Hydrogenase H2-Forming Methylenetetrahydromethanopterin Dehydrogenase As Revealed by Infrared Spectroscopy. Journal of the American Chemical Society 126(2004) 14239-14248., Mössbauer[18][18] S. Shima, E. J. Lyon, R. K. Thauer, B. Mienert, and E. Bill : Mössbauer Studies of the Iron-Sulfur-Cluster-Free Hydrogenase: The Electronic State of the Mononuclear Fe Active Site. Journal of the American Chemical Society 127(2005) 10430-10435., and EXAFS[19][19] M. Korbas, S. Vogt, W. Meyer-Klaucke, E. Bill, E. J. Lyon, R. K. Thauer and S. Shima: The iron-sulfur-cluster-free hydrogenase (Hmd) is a metalloenzyme with a novel iron binding motif. (2006). spectra revealed that the active site contains one low spin Fe (Fe(0) or Fe(II)), one S from cysteine, two CO ligands and one N from pyridone cofactor, also a possible vacant site.

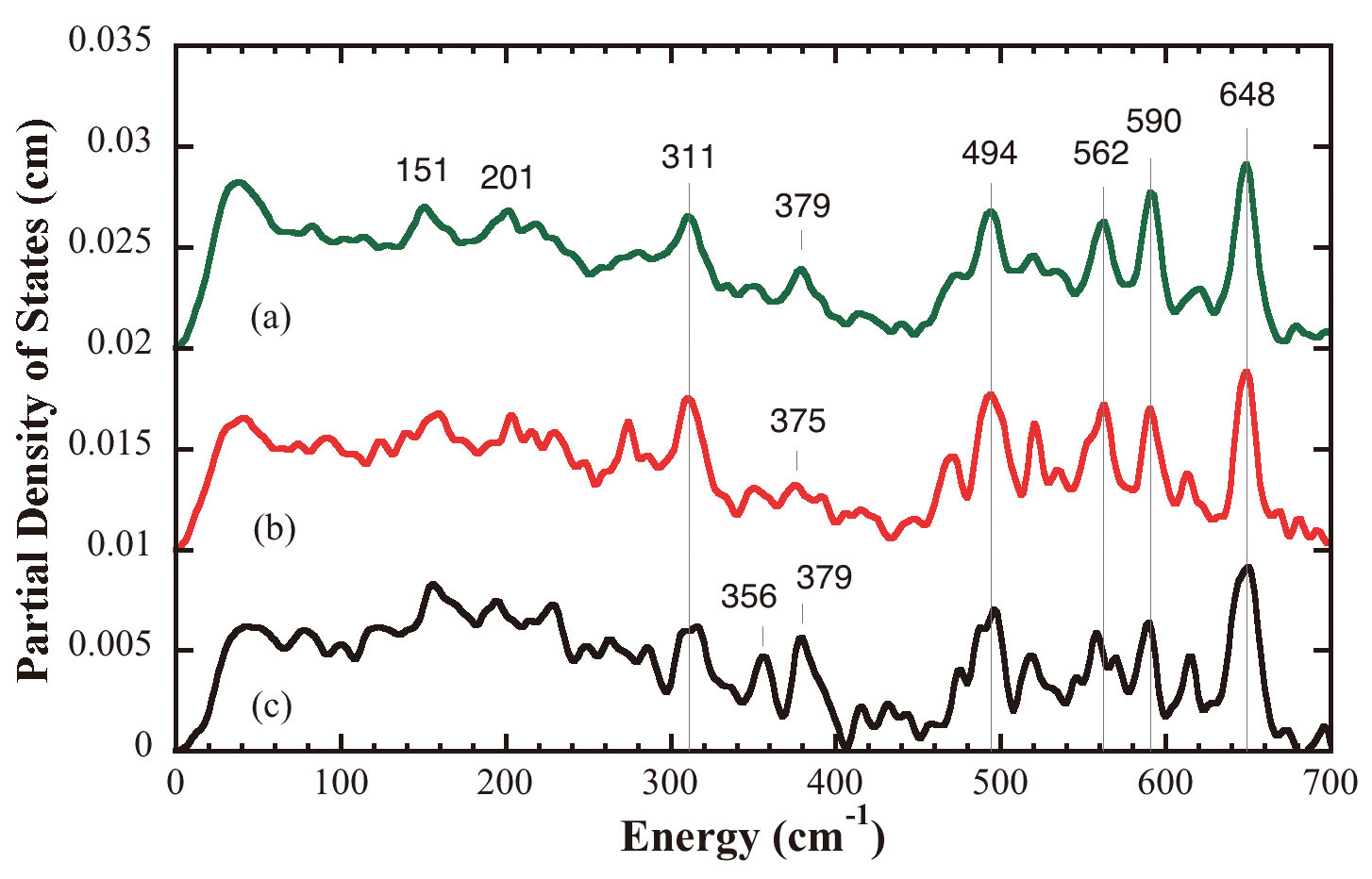

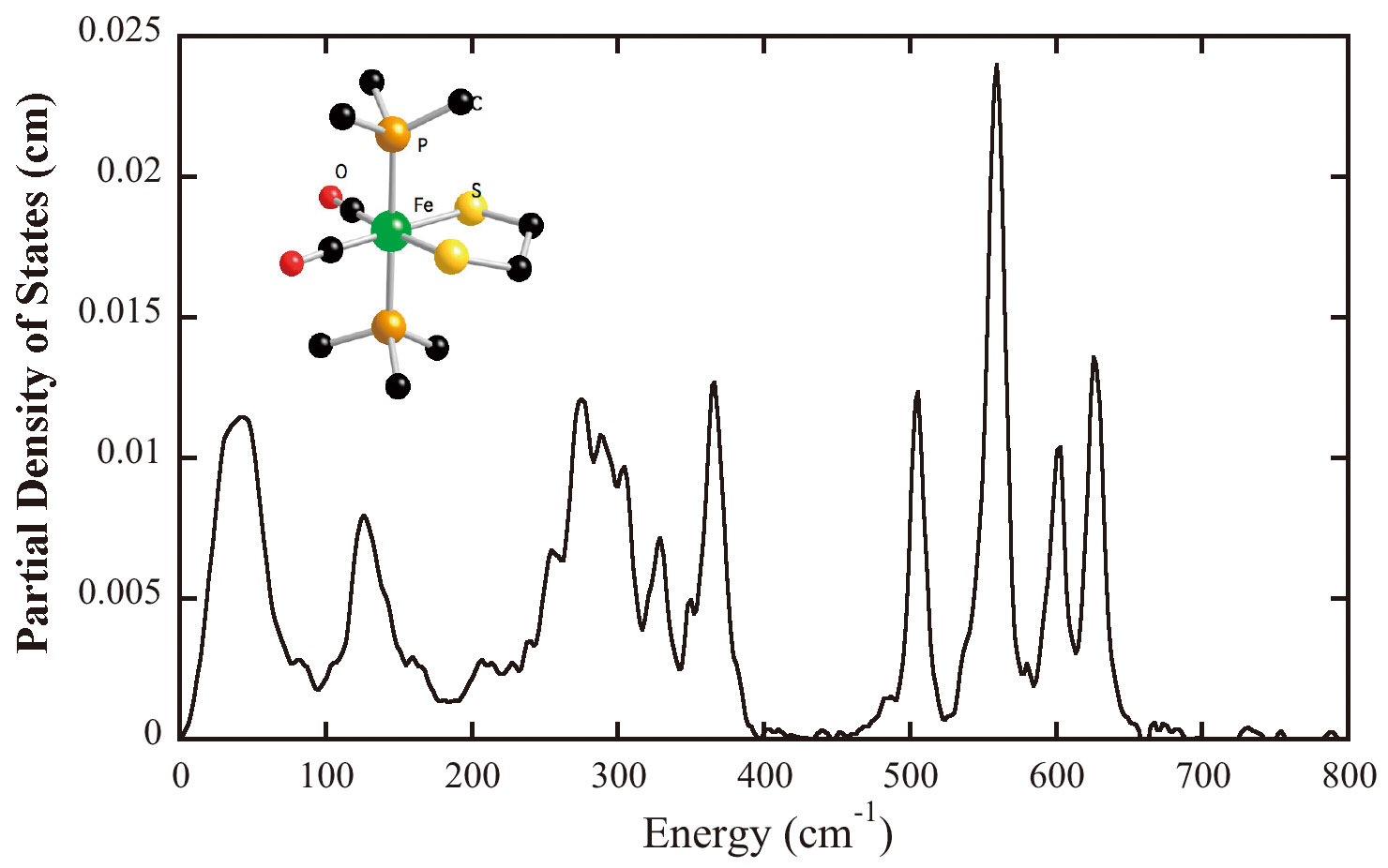

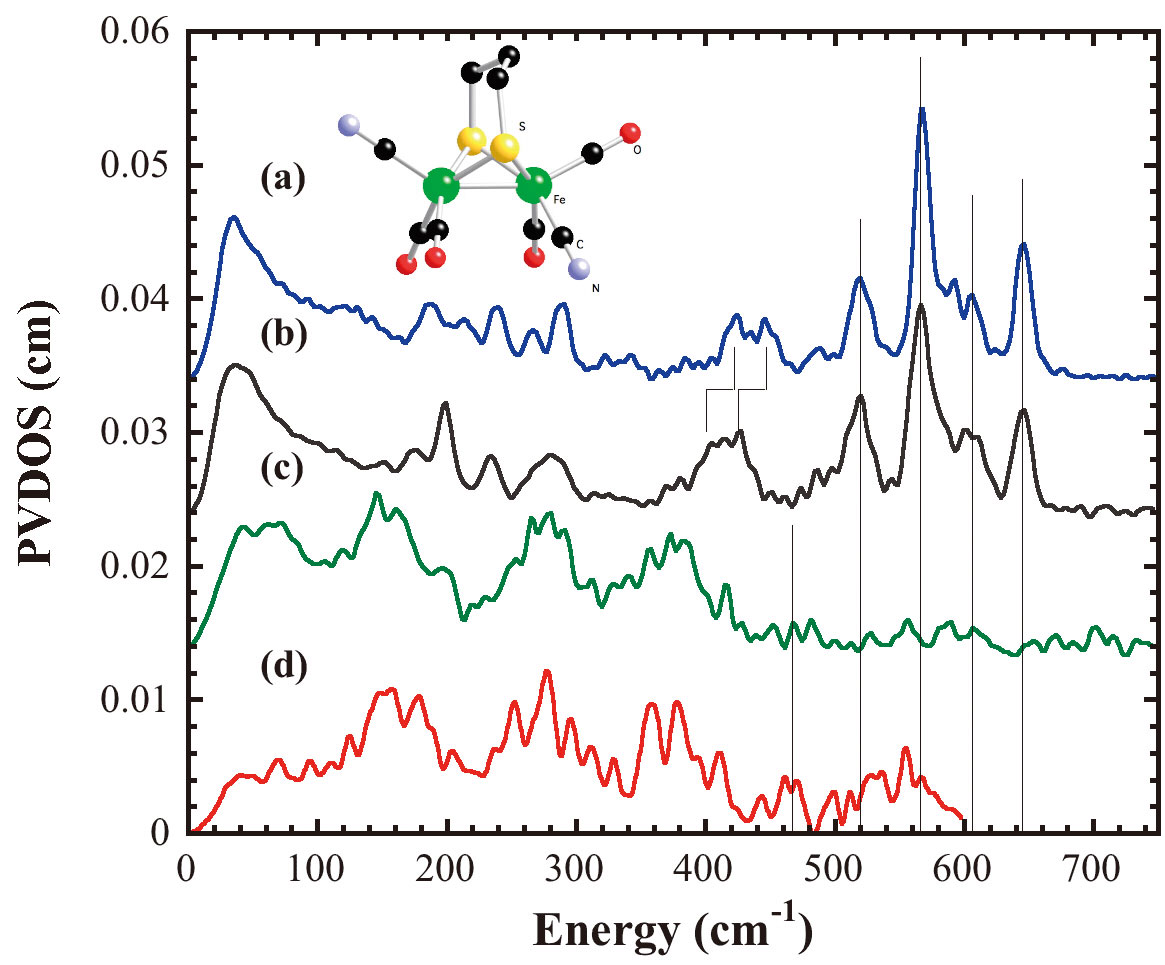

We have examined the as-isolated Hmd H2ase at pH8, the H218O exchanged Hmd H2ase at pH8, and the Hmd H2ase under the presence of H2 and methenyl-H4MPT+ at pH6. The pH8 state is thought to be enzyme resting state; the pH6 state is thought to be active state. The NRVS spectra are shown in Figure 7, they have been interpreted by comparison with a cis-(CO)2-ligated Fe model complex (Figure 7) as well as by normal mode simulations of a plausible 5-coordinated active site structure. The simulation on the as-isolated pH8 Hmd supports a cis-(CO)2 geometry for the active site of Hmd protein, also it gives further insight into the dynamics of the Fe site, revealing Fe-CO stretch and Fe-CO bend modes at 494, 562, 590, and 648 cm-1. The NRVS also reveals a band assigned to Fe-S stretching motion at 〜311 cm-1, which is observed in all Hmd samples we examined. A peak at 〜379 cm-1 is tentatively assigned to a bound water or hydroxide ligand., which is clearly seen in the pH8 and pH6 spectra, but it is significantly weaker in the H218O spectrum. We also find from the simulations that the cysteine and the pyridone ring motions definitely have noticeable contributions to the NRVS spectrum, and can influence the overall shape of the spectrum, especially for the low frequency region.

Figure 7. Top: NRVS PVDOS for (a) as-isolated Hmd in 50 mM Tricine/NaOH buffer at pH8, (b) as-isolated Hmd 50 mM Tricine/NaOH buffer exchanged in 18O water at pH8, (c) Hmd in 50 mM Mes-NaOH buffer under the presence of H2 and methenyl-H4MPT+ at pH6.0; Bottom: NRVS PVDOS of mononuclear cis-(CO)2 complex (Inset is the structure of this complex).

Application of the NRVS technique to the Hmd protein has allowed us for the first time to observe the dynamics of the Fe-CO bending and stretching motion. However, since we do not have exact structure for the active site at this moment, we will wait for the crystal structure of Hmd holo-enzyme to obtain detail simulations on the Hmd NRVS.

3.3.2 [NiFe] and [FeFe] H2ases

For [NiFe] and [FeFe] H2ases study, we still focused on revealing structure and vibrational dynamics on the Fe center of the active centers. We started from two dinuclear Fe model complexes of the [FeFe] H2ase active site, [NEt4][Fe(S2C3H6)(12CN)2(CO)4] and [NEt4][Fe(S2C3H6)(13CN)2(CO)4][20][20] F. Gloaguen, J. D. Lawrence, M. Schmidt, S. R. Wilson and T. B. Rauchfuss: Synthetic and structural studies on [Fe-2(SR)(2)(CN)(x)(CO)(6-x)](x-) as active site models for Fe-only hydrogenases. Journal of the American Chemical Society 123(2001) 12518-12527.(Figure 8). The features between 500 cm-1 and 670 cm-1 in both NRVS spectra were contributed mainly from Fe-CO stretching and bending motions. The clearly shift of the features between 400 cm-1 and 500 cm-1 was due to 12C/13C isotope shift on CN- ligands, also we observed Fe-S motions around 300 cm-1 and Fe-Fe stretching motion at 〜200 cm-1. These findings are consistent with the published resonant Raman spectra of the same model complexes[21][21] A. T. Fiedler and T. C. Brunold: Combined Spectroscopic/Computational Study of Binuclear Fe(I)-Fe(I) Complexes: Implications for the Fully-Reduced Active-Site Cluster of Fe-Only Hydrogenases. Inorganic Chemistry 44(2004) 1794-1809..

Figure 8. NRVS PVDOS of (a)[NEt4][Fe(S2C3H6)(12CN)2(CO)4], (b) [NEt4][Fe(S2C3H6)(13CN)2(CO)4], (c) as-isolated NiFe H2ase from Desulfovibrio vulgaris Miyazaki F, (d) as-isolated FeFe H2ase from Clostridium acetobutylicum; Inset is the structure of Fe(S2C3H6)(CN)2(CO)4]-.

For the real enzyme samples, we have measured the first spectra of the as-isolated [NiFe] H2ase from Desulfovibrio vulgaris Miyazaki F and the as-isolated [FeFe] H2ase from Clostridium acetobutylicum using NRVS (Figure 8). Both [NiFe] and [FeFe] H2ases have more than 10 Fe atoms in each protein molecule. Only one Fe atom for [NiFe] H2ase and two Fe atoms for [FeFe] H2ase at the active centers, other Fe atoms within each molecule are belong to FeS clusters, which involve in electron transfer pathway during the enzyme catalysis. From Figure 8, we can see that the features with large intensities between 100 cm-1 and 420 cm-1 were mainly contributed from those FeS clusters, which can be compared with our NRVS spectrum of 4Fe ferridoxin. 4Fe ferridoxin contains one 4Fe4S cluster in each molecule. The tremendous Fe sites prevent us from detail study on the active site Fe center of both [NiFe] and [FeFe] H2ases.

However, the current results do provide us with useful information. Comparing with the model complex studies and Hmd H2ase studies, the features between 500 cm-1 and 620 cm-1 in [NiFe] H2ase spectrum and the features between 480 cm-1 and 600 cm-1 in [FeFe] H2ase spectrum were possible Fe-CO stretching and bending motions contributed from Fe center of the active sites, while the features between 420 cm-1 and 500 cm-1 in [NiFe] H2ase spectrum and the features between 420 cm-1 and 480 cm-1 in [FeFe] H2ase spectrum were possible Fe-CN stretching and bending motions.

Since we have already obtained promising results on rubredoxin crystals using NRVS mentioned in Section 3.1, we are now trying to get H2ase crystals to perform crystal NRVS. In this way, we can selectively excite the vibrational modes from Fe centers at the H2ase active sites, then more clear spectra on the Fe centers can be obtained, and detailed studies can be conducted. Combined with isotopic labeling of ligands at the active sites, characterization on the structure and dynamics of the H2ase active sites using NRVS is well possible.

4. Summary

The results presented above illustrate that NRVS has a role to play in the ever increasingly complex attack on unraveling the secrets of metalloenzymes, and no doubt with continued future development will become more routine and readily available. In the future, we will pursue our single crystal work on nitrogenase and NiFe hydrogenase as well as FeMoco biosynthesis work. As and when it becomes available on BL09XU, we intend to use 61Ni NRVS of appropriate Ni models and eventually NiFe H2ase and other Ni proteins. A site-selective probe of Ni center vibration modes will be very useful and should allow major advances in understanding Ni biochemistry.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Dr. Yoshitaka Yoda for his dedication on developing BL09XU at SPring-8, and his experience and help during the three-year period of this long-term proposal. We also would like to thank all the collaborators, who have been continuously providing us excellent samples. They are Dr. Francis E. Jenney, Jr. and Prof. Michael W. W. Adams at University of Georgia, US for rubredoxin samples, Dr. Karl Fisher and Prof. William E. Newton at Virginia Tech, US for N2ase samples, Prof. Seigo Shima and Prof. Rolf K. Thauer at the Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology, Germany for Hmd H2ase, Prof. Yoshiki Higuchi at University of Hyogo, Japan for NiFe H2ase, Dr. Paul King from National Renewable Energy Laboratory, US For FeFe H2ase, and Prof. Thomas B. Rauchfuss from University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, US for H2ase active site model complexes. Finally, we would like to thank our previous group members, Mr. Philip Titler and Mr. Gregory Mcnerney for assistance with our experiments. This work was funded by NIH GM-65440 (SPC), EB-001962 (SPC), and the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research (SPC).

Publication List

1. Y. Xiao, H. Wang, S. J. George, M. C. Smith, M. W. W. Adams, J. Francis E. Jenney, W. Sturhahn, E. E. Alp, J. Zhao, Y. Yoda, A. Dey, E. I. Solomon and S. P. Cramer: Normal Mode Analysis of Pyrococcus furiosus Rubredoxin via Nuclear Resonant Vibrational Spectroscopy (NRVS) and Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. Journal of the American Chemical Society 127(2005) 14596-14606.

2. Y. Xiao, K. Fischer, M. C. Smith, W. Newton, D. A. Case, S. J. George, H. Wang, W. Sturhahn, E. E. Alp, J. Zhao, Y. Yoda and S. P. Cramer: How Nitrogenase Shakes - Initial Information about P-Cluster and FeMo-Cofactor Normal Modes from Nuclear Resonance Vibrational Spectroscopy (NRVS). Journal of the American Chemical Society 128 (2006) 7608-7612.

3. M. Tan, A. R. Bizzarri, Y. Xiao, S. Cannistraro, T. Ichiye, C. Manzoni, G. Cerullo, M. W. W. Adams, J. Francis E. Jenney and S. P. Cramer: Oberservation of Terahertz Vibrations in Pyrococcus furiosus Rubredoxin via Impulsive Coherent Vibrational Spectroscopy and Nuclear Vibrational Spectroscopy-Interpretation by Molecular Mechanics. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry 101 (2006) 375-384.

References

[1] B. E. Smith, R. L. Richards and W. E. Newton: Catalysis for Nitrogen Fixation - Nitrogenases, Relevant Chemical Models and Commerical Processes. Springer (2004).

[2] K. A. Vicent, J. A. Cracknell, A. Parkin and F. A. Armstrong: Hydrogen cycling by enzymes: electrocatslysis and implications for future energy technology. Dalton Trans. (2005) 3397-3403.

[3] O. Einsle, F. A. Tezcan, S. L. A. Andrade, B. Schmid, M. Yoshida, J. B. Howard and D. C. Rees: Nitrogenase MoFe-Protein at 1.16 Å Resolution: A Central Ligand in the FeMo-Cofactor. Science 297(2002) 1696-1700.

[4] A. Volbeda, M. H. Charon, C. Piras, E. C. Hatchikian, M. Frey and J. C. FontecillaCamps: Crystal Structure of the Nickel-Iron Hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio gigas. Nature 373(1995) 580-587.

[5] J. W. Peters, W. N. Lanzilotta, B. J. Lemon and L. C. Seefeldt: X-ray Crystal Structure of the Fe-Only Hydrogenase (CpI) from Clostridium pasteurianum to 1.8 Angstrom Resolution. Science 282(1998) 1853-1858.

[6] J. T. Sage, C. Paxson, G. R. A. Wyllie, W. Sturhahn, S. M. Durbin, P. M. Champion, E. E. Alp and W. R. Scheidt: Nuclear resonance vibrational spectroscopy of a protein active-site mimic. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 13(2001) 7707-7722.

[7] Y. Yoda, M. Yabashi, K. Izumi, X. W. Zhang, S. Kishimoto, S. Kitao, M. Seto, T. Mitsui, T. Harami, Y. Imai and S. Kikuta: Nuclear resonant scattering beamline at SPring-8. Nuclear Instruments & Methods in Physics Research Section A-Accelerators Spectrometers Detectors & Associated Equipment 467(2001) 715-718.

[8] S. Kishimoto, Y. Yoda, M. Seto, S. Kitao, Y. Kobayashi, R. Haruki and T. Harami: Array of avalanche photodiodes as a position-sensitive x-ray detector. Nuclear Instruments & Methods In Physics Research Section A 513(2004) 193-196.

[9] J. Meyer, and J.-M. Moulis: Rubredoxin, in Handbook of Metalloproteins (A. Messerschmidt and R. Huber, Eds.) Wiley, New York. (2001) pp505-517.

[10] R. Bau, D. C. Rees, D. M. Kurtz, R. A. Scott, H. S. Huang, M. W. W. Adams and M. K. Eidsness: Crystal structure of rubredoxin from Pyrococcus furiosus at 0.95Å resolution, and the structures of N-terminal methionine and formylmethionine variants of Pf Rd. Contributions of N-terminal interactions to thermostability. Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry 3(1998) 484-493.

[11] R. S. Czernuszewicz, L. K. Kilpatrick, S. A. Koch and T. G. Spiro: Resonance Raman Spectroscopy of Iron(III) Tetrathiolate Complexes: Implications for the Conformation and Force Field of Rubredoxin. Journal of the American Chemical Society 116(1994) 1134-1141.

[12] Y. Xiao, H. Wang, S. J. George, M. C. Smith, M. W. W. Adams, J. Francis E. Jenney, W. Sturhahn, E. E. Alp, J. Zhao, Y. Yoda, A. Dey, E. I. Solomon and S. P. Cramer: Normal Mode Analysis of Pyrococcus furiosus Rubredoxin via Nuclear Resonant Vibrational Spectroscopy (NRVS) and Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. Journal of the American Chemical Society 127(2005) 14596 -14606.

[13] D. C. Rees, F. A. Tezcan, C. A. Haynes, M. Y. Walton, S. Andrade, O. Einsle and J. B. Howard: Structural basis of biological nitrogen fixation. Philosophical TRANSACTIONS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF LONDON SERIES A 363(2005) 971-984.

[14] Y. Xiao, K. Fischer, M. C. Smith, W. Newton, D. A. Case, S. J. George, H. Wang, W. Sturhahn, E. E. Alp, J. Zhao, Y. Yoda and S. P. Cramer: How Nitrogenase Shakes - Initial Information about P-Cluster and FeMo-Cofactor Normal Modes from Nuclear Resonance Vibrational Spectroscopy (NRVS). Journal of the American Chemical Society 128(2006) 7608-7612.

[15] M. Frey : Hydrogenases: Hydrogen-Activating Enzymes. ChemBioChem 3(2002) 153-160.

[16] S. Shima and S. K. Thauer: A Third Type of Hydrogenase Catalyzing H2 Activation. The Chemical Record 7(2007) 37-46.

[17] E. J. Lyon, S. Shima, R. Boecher, R. K. Thauer, F.-W. Grevels, E. Bill, W. Roseboom and S. P. J. Albracht: Carbon Monoxide as an Intrinsic Ligand to Iron in the Active Site of the Iron-Sulfur-Cluster-Free Hydrogenase H2-Forming Methylenetetrahydromethanopterin Dehydrogenase As Revealed by Infrared Spectroscopy. Journal of the American Chemical Society 126(2004) 14239-14248.

[18] S. Shima, E. J. Lyon, R. K. Thauer, B. Mienert, and E. Bill : Mössbauer Studies of the Iron-Sulfur-Cluster-Free Hydrogenase: The Electronic State of the Mononuclear Fe Active Site. Journal of the American Chemical Society 127(2005) 10430-10435.

[19] M. Korbas, S. Vogt, W. Meyer-Klaucke, E. Bill, E. J. Lyon, R. K. Thauer and S. Shima: The iron-sulfur-cluster-free hydrogenase (Hmd) is a metalloenzyme with a novel iron binding motif. (2006).

[20] F. Gloaguen, J. D. Lawrence, M. Schmidt, S. R. Wilson and T. B. Rauchfuss: Synthetic and structural studies on [Fe-2(SR)(2)(CN)(x)(CO)(6-x)](x-) as active site models for Fe-only hydrogenases. Journal of the American Chemical Society 123(2001) 12518-12527.

[21] A. T. Fiedler and T. C. Brunold: Combined Spectroscopic/Computational Study of Binuclear Fe(I)-Fe(I) Complexes: Implications for the Fully-Reduced Active-Site Cluster of Fe-Only Hydrogenases. Inorganic Chemistry 44(2004) 1794-1809.

Stephen P. Cramer

Department of Applied Science, University of California, Davis

One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616, USA

TEL : (+1)530-752-0360 FAX : (+1)530-752-2444

e-mail : spcramer@ucdavis.edu